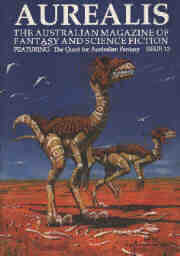

Aurealis #114

$3.99

This issue has stories that traverse the vast expanse of speculative fiction. Sarah Napier’s story, ‘Fail’, asks how we might deal with virtual infidelity in the face of ever-evolving technologies. In ‘A Figure in the Haze’, Rebecca Boyle explores the horror of ordinary people lured into corruption, while James Rowland’s ‘The Glassblower’s Peace’ conjures some unusual magic in Renaissance Venice.

All Aurealis store prices are in USD

- From the Cloud — Dirk Strasser

- Fail — Sarah Napier

- A Figure in the Haze — Rebecca Boyle

- The Glassblower’s Peace — James Rowland

- The Gothic Trail – The Guardian’s Place in Australian Gothic Tradition — Gillian Polack

- Psychological Science Fiction and Our Fascination with Inner Space — Lachlan Walter

A number of years ago, when Aurealis was a print-only magazine, we regularly applied for grants from various bodies such as the Australia Council and Arts Victoria. We were competing for funding with well-established literary magazines such as Meanjin, Overland and Quadrant. The funding always went directly to increasing author payment levels, so we felt it was worth the effort. It was always a difficult and time-consuming process to fulfil all the requirements of an application. We were successful on five occasions, but we also had a long string of unsuccessful applications. The biggest sticking point was always the requirement to demonstrate ‘literary merit.’ Surely only a reading of the stories can demonstrate that.

But that’s where a magazine of fantasy and science fiction is at a distinct disadvantage.

At the end of 2017 the results of a research project called The Genre Effect study were published in the journal Scientific Study of Literature. It was undertaken by Professors Chris Gavaler and Dan Johnson from Washington and Lee University.

Around 150 participants were given a text of 1000 words to read. Half were given a ‘literary’ version of the text and the other a ‘science fiction’ version. The texts were identical except in the literary version, the main character enters a diner while in the science fiction version, he enters a galley in a space station inhabited by aliens and androids as well as humans. The only differences between the two were setting-related. For example, the literary version used the word ‘door’ and the science fiction version used the word ‘airlock.’

After the reading, the participants were asked to comment on the literary merit of the story they had read. They were asked how much effort they spent trying to work out what the characters were feeling, and how much they agreed with statements such as ‘I felt like I could put myself in the shoes of the character in the story.’

The study exposed a self-fulfilling bias among literary readers against science fiction, demonstrating that science fiction is currently still unfairly viewed in academia.

Here are some of the results from the study:

‘Converting the text’s world to science fiction dramatically reduced perceptions of literary quality, despite the fact participants were reading the same story in terms of plot and character relationships.’ The readers of the science fiction version generally scored lower in comprehension. They ‘reported exerting greater effort to understand the world of the story, but less effort to understand the minds of the characters.’

The professors also reported that readers of the science fiction version of the story ‘appear to have expected an overall simpler story to comprehend, an expectation that overrode the actual qualities of the story itself… the science fiction setting triggered poorer overall reading and appears to predispose readers to a less effortful and comprehending mode of reading—or what we might term non-literary reading—regardless of the actual intrinsic difficulty of the text.’

Professor Gavaler says, ‘those who are biased against SF, thinking of it as an inferior genre of fiction, they assume the story will be less worthwhile, one that doesn’t require or reward careful reading, and so they read less attentively… It’s a self-fulfilling bias—except we can now show objectively that the weakness is with the reader, not the story itself.’ He adds, ‘if you’re stupid enough to be biased against SF you will read SF stupidly.’ He is interested in exploring this Genre Effect further and discovering whether fantasy tropes such as a sorcerer’s wand would have similar effects on readers.

These results are not a surprise to those of us who have been involved in science fiction publishing over the years and explains the issues we had when applying for grants in the past. As Professor Gavaler says, while it’s disappointing that these biases exist, at least now they’ve been exposed.

All the best from the cloud.

Dirk Strasser

From Fail by Sarah Napier:

Some days, you just shouldn’t come into work.

From A Figure in the Haze by Rebecca Boyle:

Kendrick checked the Collector, nodded, and produced an envelope from his jacket pocket. I didn’t count it, just slipped it quickly into my handbag. The noise of the beer garden rose around us. The laughter, the clinking glasses. I wondered if anyone had noticed our transaction. I didn’t want to look like a drug dealer.

From The Glassblower’s Peace by James Rowland:

Tomaso da Guda chose to remember only one thing about his father: he had too many sons. The proper amount was three. With three able-bodied men, a man could plant his seed into the most important areas of Venetian life. The eldest would be trained to go into government. The next would receive some patronage from a rich merchant and be given a berth on his most profitable ship. The youngest would be given to the clergy; it was important to have a direct route into Heaven. Tomaso da Guda knew all this because his father told him these simple truths on his deathbed. Tomaso was his fourth son. He was left to float rudderless through the canals of the city.

From The Gothic Trail – The Guardian’s Place in Australian Gothic Tradition by Gillian Polack:

When I was in my teens, we listed cultural influences boldly and bravely. We actively tried to develop an Australian culture through combatting them. We fought this battle with huge baggage. That baggage included a cultural cringe that was magnificent in the weight it forced us to bear as we wrote, drew and dreamed.

From Psychological Science Fiction and Our Fascination with Inner Space by Lachlan Walter:

There’s no denying that the world of today resembles the science fiction futures imagined by writers of the past. From smartphones to driverless cars, social media to online shopping, holographic recreations of dead musicians to robotic concierges, retinal scanners and facial-recognition systems to talking computers and drones, advanced technology is inextricably intertwined with our lives. In fact, so ubiquitous has it become, that it has left hitherto unseen mental disorders and psychological problems in its wake.