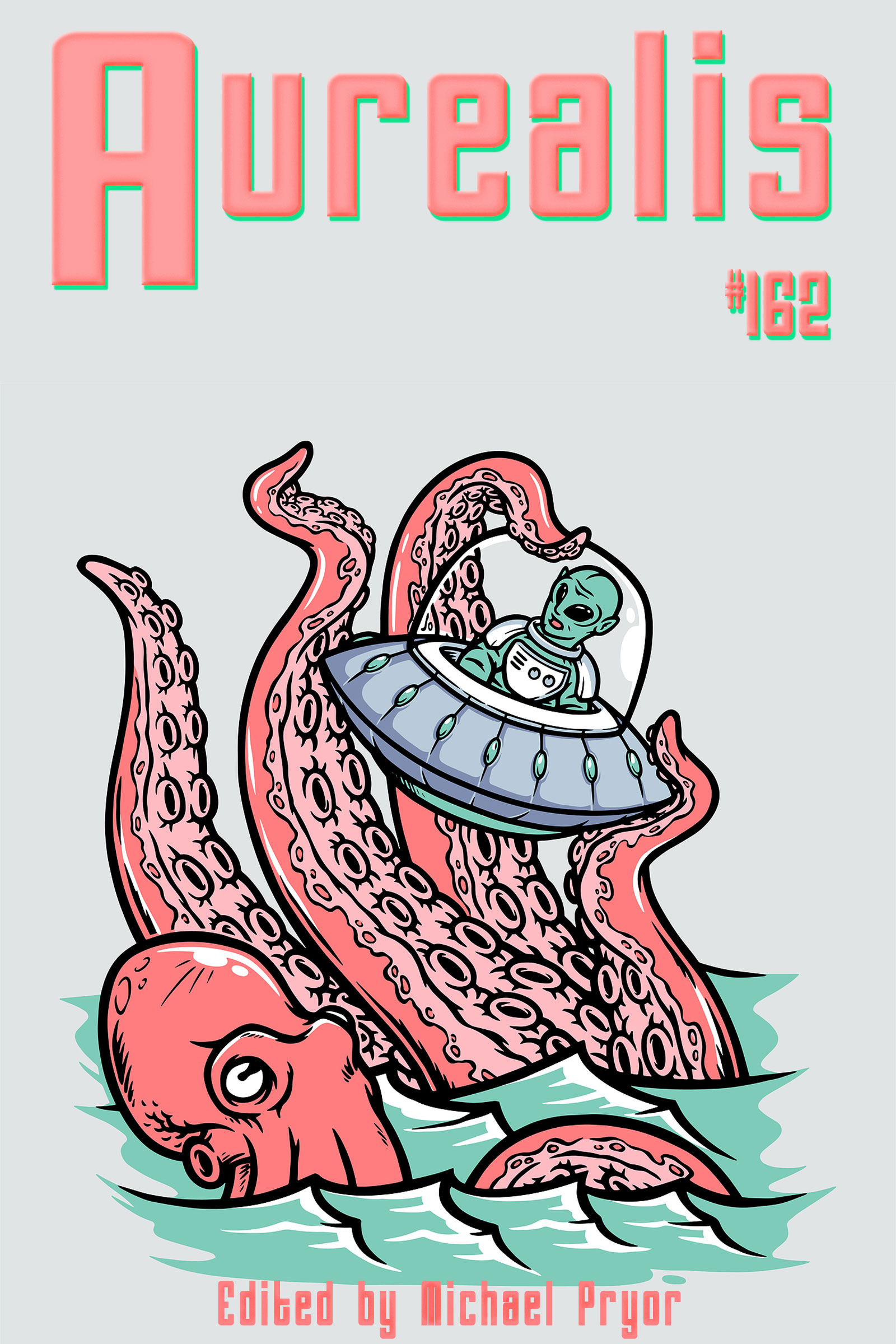

Aurealis #162

$3.99

In Aurealis #162 we present compelling fiction by Edward Brauer, Imogen Cassidy and Desmond Astaire. Our superb internal art comes from Lynette Watters, Kim Lennard and Rebecca Stewart while our engrossing non-fiction is from Lynne Lumsden Green, Rebecca Langham and Gillian Polack. And don’t forget our outstanding Reviews section curating a multitude of books for your consideration. Aurealis—is it too good to be true?

- From the Cloud — Michael Pryor

- Enter the Bubble — Edward Brauer

- Sister Snips — Imogen Cassidy

- The Otherworld Theory — Desmond Astaire

- Pioneering SF Women: The Critique and Commentary of Joanna Russ — Lynne Lumsden Green

- What is it About Zombies? — Rebecca Langham

- Winifred Law's Lost Adventures — Gillian Polack

- Why Sissy is the Perfect Post-modern Slasher for the Social Media Generation — Zachary Ashford

Lee Harding died on 19 April this year, and Aurealis has been remiss in not acknowledging the passing of one of the seminal figures in Australian SF.

Bruce Gillespie has put together the most detailed tribute to this fan, writer and editor extraordinaire (file770.com/hard-to-believe-hes-no-longer-with-us-lee-harding-1937-2023/) and Wikipedia has an accurate and complete entry, so we’re not going to go over that ground. Instead, we want to concentrate on the book that is Harding’s masterpiece, the one that had the most impact, the one that is his lingering legacy: Displaced Person (1979).

For a long time in the 1980s, Displaced Person featured as a set text in many, many English classrooms across the country. For a genre novel, this is an extraordinary feat, and it speaks for the novel’s impact. It was a staple and introduced many young readers to the entire concept of SF literature. Some of those who read Displaced Person back then are the grown-up SF readers of today.

Displaced Person is an unsettling story of alienation, and the metaphor of the central conceit is such a perfect capturing of the difficulties of teenage life that Graeme Drury’s story has a resonance that has endured.

In it, Graeme gradually becomes trapped in a world that he sees as fading away, only to find, painfully, that he himself is becoming invisible to those around him. He transitions to being unnoticed, unremarked, gone. He is in a displaced limbo.

In some ways it’s the mundanity of the world Graeme loses that makes the novel all the more poignant. It’s clearly modern-day Australia, Melbourne with ordinary domestic details, ordinary streets, ordinary lives, but a place that Graeme finds he has no place in.

Displaced Person was winner of the 1980 Book of the Year Award from the Children’s Book Council of Australia, a clear recognition of the quality and power of this important novel.

Vale, Lee Harding.

All the best from the cloud!

Michael Pryor

From Enter the Bubble by Edward Brauer:

Martins wasn’t kidding, they were close. The Bubble reared up above them into the clouds, a seething jumble of facades, for-sale signs and Astroturf that shifted and breathed like some mucosal egg. They’d long since cleared the final checkpoint, and the freeway was barren but for their trio of vans and the vast obscenity before them.

From Sister Snips by Imogen Cassidy:

Sister Nine dreams of Uncle Eleven. She can feel the warmth of his larger hand over hers as he guides her in the steps to lay out her tools for surgery. She can feel the difference in the texture of his skin, in the rough dry pads of his fingers. There is kindness in that touch. Something gentle and comforting in the sterile white of the training room.

From The Otherworld Theory by Desmond Astaire:

Brandi Esken is thirty-two, but she’s aged twice as much in the five years since the night her significant other vanished. Her once-vibrant eyes have dulled, and anxiety has imprinted deep lines into her face.

From Pioneering SF Women: The Critique and Commentary of Joanna Russ by Lynne Lumsden Green:

Joanna Russ was born in New York in 1937; she grew up to become a feminist writer, challenging sexist views during the 1970s and 1980s. She graduated from Cornell University, in 1957, and received her Masters in Fine Arts from the Yale Drama School in 1960. A writer from an early age, she used her intellect and sharp humour to write novels, short stories, and nonfiction works. These days, she is best remembered for her award-winning novel, The Female Man (1975), and her brilliant books of literary criticism. She was nominated and won Nebula, Locus, Pilgrim, and Hugo awards, and posthumously won two James Tiptree Jr awards. She died of a stroke in 2011.

From What is it About Zombies? by Rebecca Langham:

Zombies have become an undeniable staple of the horror genre, appearing in countless films, television shows, and video games. They’ve also been the subject of numerous academic studies, and their popularity has only continued to grow. Zombies have become so ubiquitous in popular culture that they have even inspired their own subculture. There are zombie walks, where people dress up as zombies and parade through the streets, as well as zombie-themed events, such as run-for-your-life obstacle courses. These events serve as a testament to the enduring popularity of the zombie genre and its ability to captivate audiences across generations.

From Winifred Law's Lost Adventures by Gillian Polack:

Many Australian writers seem to fall into a ‘let us forget’ category. So many fall into the piles of literary regret and forget. Take Winifred Law, for instance, whose two novels were published in the 1940s. Through Space to the Planets was published in 1944 and republished in 1946 (and ran to three editions), and Rangers of the Universe was issued in 1945 and again in 1946.

From Why Sissy is the Perfect Post-modern Slasher for the Social Media Generation by Zachary Ashford:

Given the nature of social media, it’s no surprise that the world is awash with disinformation and the unfiltered ‘expertise’ of unqualified professionals. What is surprising is that it’s taken so long for horror to seriously tackle the issue. Thankfully, Hannah Barlow and Kane Senes, two Australian writer-directors have done just that, and Sissy (2022) might be the perfect post-modern slasher for the social media generation.