By Lachlan Walter

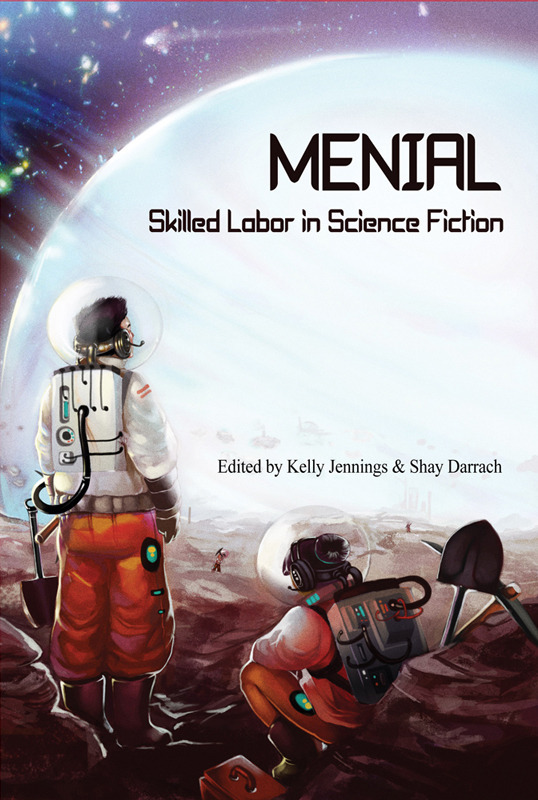

I was in my favourite second-hand bookshop the other day, looking for something new to read, something unexpected, something that I hadn’t already contemplated too many times to count. I browsed and browsed, and found nothing. And then, half-hidden by the inevitable pile of Analog magazines, I found a copy of Menial: Skilled Labour in Science Fiction, a collection of short stories edited by Shay Darrach and Kelly Jennings.

Wow. Just wow.

Wow. Just wow.

Before I become too effusive, it’s probably best to mention that not every single story in Menial is great (as always, I won’t name names here). This isn’t that uncommon when it comes to short story collections, and when we talk about great collections, the dullards and the duds can often make the diamonds shine brighter.

This is how it is with Menial.

However, its real impact and its true originality live within its theme, which is probably best paraphrased as, ‘“ordinary” workers as science fiction heroes’. Now, any science fiction fan with even a passing knowledge of the genre would probably be aware of the existence of this type of hero. Various novelists and short story writers have either used them or employed the type as prominent secondary characters, including Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, Phillip K Dick and John Brunner. Acclaimed screenwriter Dan O’Bannon created two seminal science fiction films centred on blue-collar heroes in Dark Star (1974) and Alien (1979). The mise-en-scene of blue-collar homes, workplaces and lifestyles has almost become the default setting for the vast majority of contemporary science fiction that aims to be serious, realist, or dark and gritty.

But what Menial does differently is bring these types of stories together as a whole. Instead of seeing them as simply picks from the pack that exhibit a point of difference, their existence as a collection allows a certain continuity of thought to occur; ideas and themes provoked and presented by each individual story are easily allowed to grow and flourish, thanks to further complimentary ideas and themes provided by the subsequent stories. The further I read through it, the richer the food for thought provided by these types of stories.

Menial finally left me wondering just what it is that makes blue-collar science fiction so different from regular science fiction.

And what does blue-collar science fiction actually do?

The first thing that makes it different is so obvious as to be staring us in the face: it shows us the existence of the ‘ordinary’ person (and, by de-facto, an ‘ordinary’ world). The existence of something so seemingly banal as ‘the ordinary’ is an aspect of science fiction that many writers tend to normally gloss over or ignore, and so accustomed are we to seeing science fiction heroes personified as either professionals and authority figures, or as belonging to what we could call the ‘underground’, that we often don’t even question these personifications.

As an example, which one of these different character groups seems a lesser embodiment of science fiction than the others? A ‘professional’ group of scientists, inventors, programmers, doctors, astronauts, politicians, bureaucrats, soldiers and military paper-shufflers? An ‘underground’ group of criminals, private detectives, blackmarket couriers, hackers, activists, punks and cyberpunks? Or an ‘ordinary’ or blue-collar group of bricklayers, waiters, labourers, bank-tellers, shop assistants, kitchenhands, posties, plumbers, gardeners, cleaners, orderlies, street-sweepers, garbos and sandwich hands?

If the last group seems more like the cast of a Mike Leigh film than typical science fiction characters, the answer as to why there should be more blue-collar science fiction has been answered. After all, what makes the last group’s stories less important than those belonging to scientists and soldiers, or those belonging to criminals and private detectives?

By using ‘ordinary’ workers as the heroes of their stories, authors aren’t just showing us a side of the genre that is too-often absent—they are also making the genre more relatable. While some of us may actually work in jobs that would fit into the professional group, it’s probably fair to say that most, if not all of us, have worked far less glamorous jobs at some point in our lives. Waiting tables, working in a shop, washing dishes, mowing lawns, serving fast-food, cleaning houses, labouring for builders—these are the most blue-collar of blue-collar jobs, and are probably how most of us got a start in paid employment. When science fiction stories are focused around characters employed in these kinds of occupations—characters who consequently live more blue-collar lifestyles and, stereotypically, have more down-to-earth attitudes—our ability to engage with them is strengthened because we have so much more in common with them. Professional characters tend to either act as an expression of wish fulfilment for those of us still engaged in blue-collar employment, or serve as a throwback to the genre’s roots in real science and science-philosophy; underworld characters reflect the still pervasive influence of crime fiction and noir upon the genre. Blue-collar characters normally serve to ground the genre in a facsimile of reality, a facsimile in which we can see our science fiction reflection.

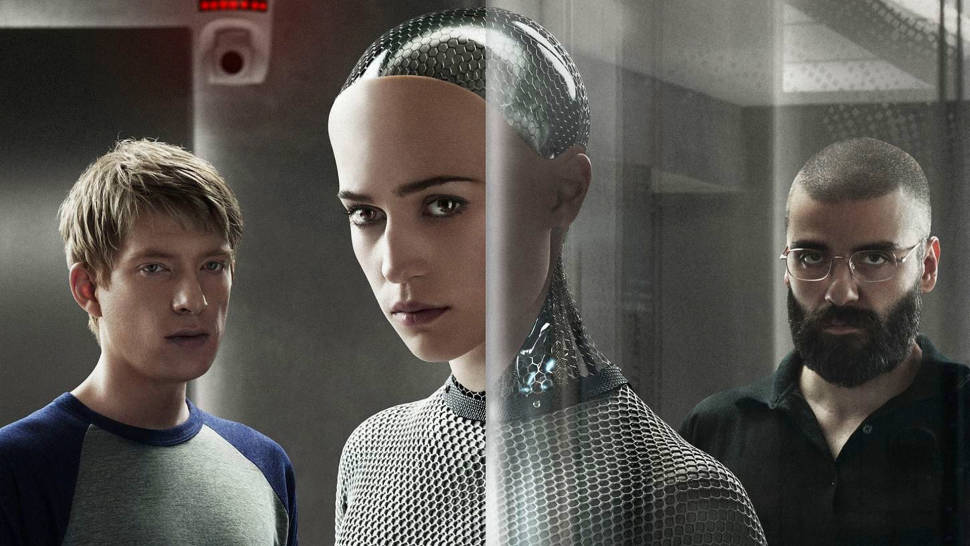

The crew of Alien are an excellent example of this. While they are technically astronauts—they are travelling through space, after all—theirs is a life more akin to that of a truck driver, a crane operator, a baggage handler or a labourer. They complain about their pay and the conditions they have to work in; they form cliques and circles within the larger group; a hierarchy exists, with status determined by pay grade. And to top it off, their ship is functional and utilitarian, more a factory or warehouse than a high-tech thing of beauty. We’ve probably all been where they are, aside from the science fiction trappings. This means that when the drama kicks in and the crew are faced with danger, the empathy we feel for them is deeper than it might usually be and we can better relate to the choices they make and the way they react.

An excellent example from Menial is Jasmine M Templet’s ‘Leviathan’, which tells the story of a newly employed janitor at a seedy office building in a vaguely dystopian future. This dystopian future is masterfully sketched, albeit in broad strokes. Both this dystopian future and the ‘take it as it comes’ attitude bestowed upon the janitor by Templet bring to mind the themes and setting and overall vibe of Ray Bradbury’s ‘The Highway’, a wonderful blue-collar science fiction story. The actual event that shaped the worlds lived in by the farmers of ‘The Highway’ and the janitor of ‘Leviathan’ doesn’t really matter to them. In the end, despite what seem like massive changes to the societies that they are a part of, their shared way of life remains the same: farm or clean, work hard for little pay. And without spoiling the ending, the unnamed janitor’s reaction to the final revelation of ‘Leviathan,’ whereby he simply accepts his duties in his stride, perfectly encapsulates the ability of blue-collar science fiction to provide a more grounded perspective on fantastical worlds than that of regular science fiction.

The other important thing that blue-collar science fiction can help facilitate is world building. How many times have we read or seen science fiction that is ultimately nothing but a lofty structure supported by some flimsy two-by-fours? To best explain this, you’ll have to forgive me for indulging in a little pop-culture citation:

A construction job of that magnitude would require a helluva lot more manpower than the Imperial army had to offer. I’ll bet there were independent contractors working on that thing: plumbers, aluminum siders, roofers… All those innocent contractors hired to do a job were killed—casualties of a war they had nothing to do with.

-Randal Graves, from Kevin Smith’s Clerks (1994), talking about the second Death Star from George Lucas’ Return of the Jedi (1983)

While Lucas undoubtedly deserves praise for the sheer depth and span of his universe—think the Mos Eisley Cantina scene, or the meetings of the Galactic Senate in the prequels—I found that the above quote built Lucas’ world much more thoroughly than any ‘wretched hive of scum and villainy’ or any of a thousand different CGI crowds. When I mull over Smith’s words, I can imagine these ‘plumbers, aluminium siders and roofers’ who brought those magnificent spaceships to life, as well as all the other ordinary people and blue-collar workers who logically must exist within Lucas’ universe, cleaning up after all those Jedi Knights or serving food to all those Galactic Senators. Suddenly, a universe that was already pretty big is now enormous, and is also much more diverse than we first thought.

While Lucas undoubtedly deserves praise for the sheer depth and span of his universe—think the Mos Eisley Cantina scene, or the meetings of the Galactic Senate in the prequels—I found that the above quote built Lucas’ world much more thoroughly than any ‘wretched hive of scum and villainy’ or any of a thousand different CGI crowds. When I mull over Smith’s words, I can imagine these ‘plumbers, aluminium siders and roofers’ who brought those magnificent spaceships to life, as well as all the other ordinary people and blue-collar workers who logically must exist within Lucas’ universe, cleaning up after all those Jedi Knights or serving food to all those Galactic Senators. Suddenly, a universe that was already pretty big is now enormous, and is also much more diverse than we first thought.

This line of thinking, however, isn’t solely confined to the Star Wars universe. Instead, we can apply it to any science fiction world. After all, someone had to build those spaceships; someone has to grease their engines. And all those shining futuristic cities? Someone had to dig the foundations; someone has to sweep the streets; someone has to collect the rubbish. I would argue that every (every!) single piece of science fiction has within its world some connection to ‘the ordinary’ and to blue-collar people, but unfortunately, they are more often than not ignored or glossed over. This is to their detriment, as instead of seeing a whole we’re just seeing a part.

Blue-collar science fiction shows us this whole. Its ordinary heroes, by their very definition, serve to flesh out the different levels that exist within society. And by telling the story of an individual whose lot in life is more like that lived by the vast majority of the population, writers of blue-collar science fiction aren’t just creating stories that are more relatable. Instead, they are also giving us access to future-worlds from the bottom up, and showing us wonders and marvels from a more grounded perspective.

Rush out and get yourself a copy of Menial. You won’t regret it.

For more by Lachlan Walter, check out his previous work in the Apocalypse Soon-ish series of articles.

If you (or someone you know) are interested in writing for the Aurealis blog from time to time, message us either through our Facebook site or send an email to lachlan.shrives@gmail.com, and we can have a chat.

Issue #83 of Aurealis is out now, abounding with Brave New Worlds!

Issue #83 of Aurealis is out now, abounding with Brave New Worlds!

To cause us further worry, fans of Australian genre-fiction cherish Miller’s original Mad Max series. Its lived-in world, deeply-set sense of place, larrikin sense of humour and almost-punkish DIY ethos are ‘Australian-isms’ that we were all proud to see enshrined on screen in such fresh and original ways, and none of us wanted to see Miller tarnish this legacy.

To cause us further worry, fans of Australian genre-fiction cherish Miller’s original Mad Max series. Its lived-in world, deeply-set sense of place, larrikin sense of humour and almost-punkish DIY ethos are ‘Australian-isms’ that we were all proud to see enshrined on screen in such fresh and original ways, and none of us wanted to see Miller tarnish this legacy.